La fusione fredda

La fusione freddaMemorie e testimonianze di un'entusiasmante avventura scientifica 1989 - 1996 |

|

|

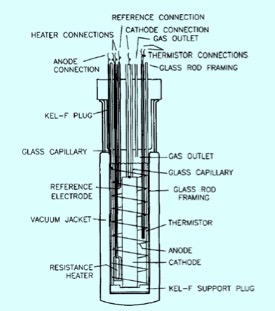

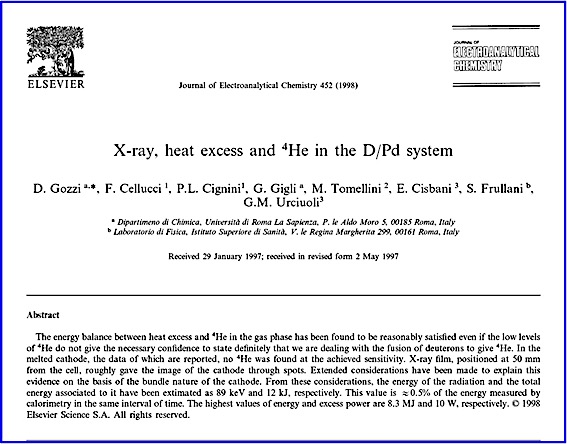

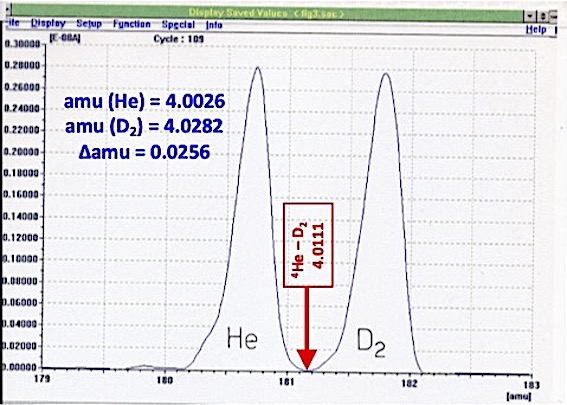

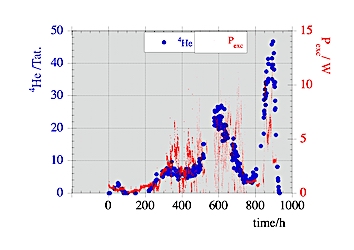

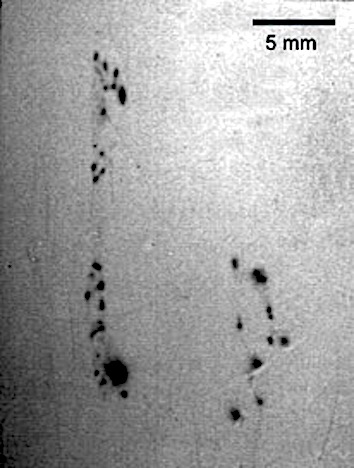

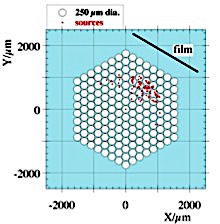

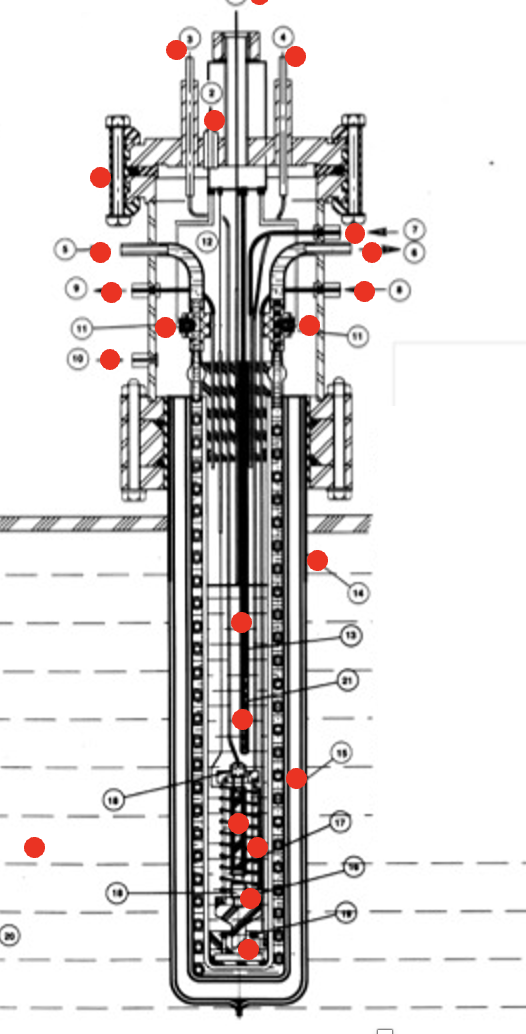

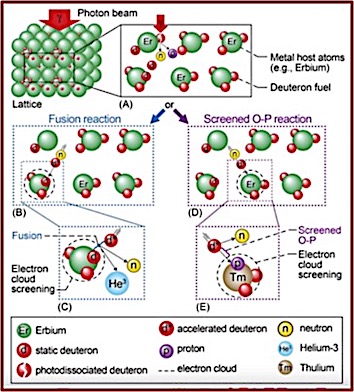

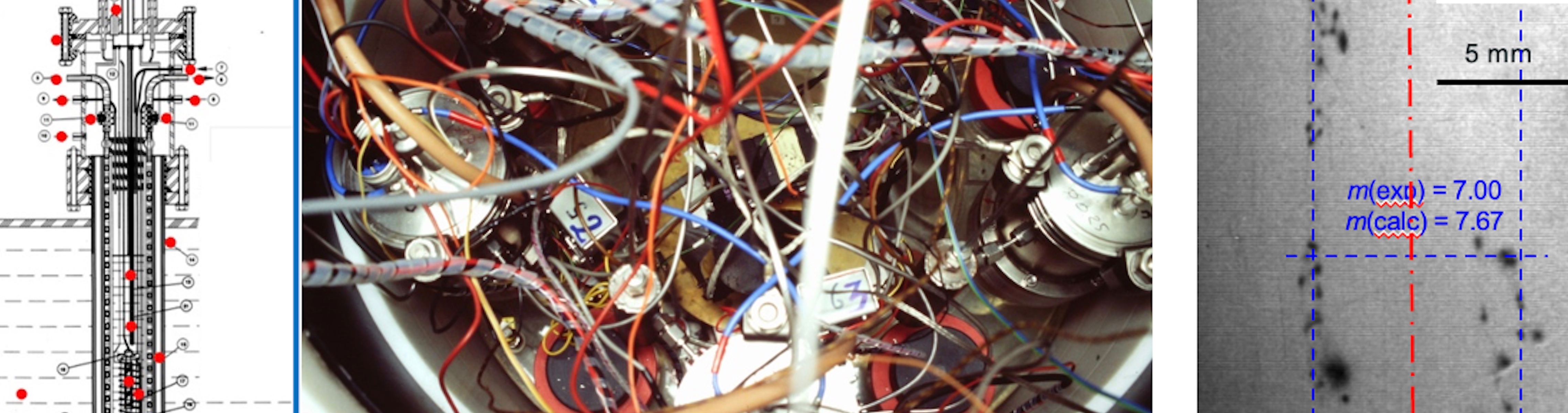

Il 23 marzo 1989 Martin Fleischmann e Stanley Pons comunicarono che in un semplice esperimento di elettrolisi in acqua pesante (D2O) con catodo di palladio (Pd) il calore misurato era maggiore di quello prodotto nella reazione di dissociazione elettrolitica di D2O. Se lo stesso esperimento era condotto con catodo di platino (Pt) il bilancio di energia era nullo. Poiché nessun effetto chimico e/o chimico-fisico ipotizzabile poteva essere responsabile di un bilancio di energia significativamente diverso da zero, essi ipotizzarono reazioni di fusione nucleare di nuclei di deuterio nella struttura di Pd. Nacque la fusione fredda. L’annuncio creò in tutto il mondo: immediato entusiasmo e persistente scetticismo. Il primo perché s’intravvedeva la possibilità di energia a basso costo e di facile produzione senza ricorrere alla fusione calda che né allora né oggi, nonostante investimenti giganteschi, non ha prodotto ancora energia disponibile. Il secondo connesso con la scarsa riproducibilità del fenomeno e soprattutto perché la fisica nucleare non prevede reazioni di fusione a bassa energia. La fusione nucleare tra nuclei, preferibilmente leggeri richiede altissime energie che si possono ottenere o sulla Terra, nella collisione in alto vuoto di nuclei accelerati in macchine come LHC del CERN di Ginevra, o nelle stelle a temperature di miliardi di °C. Sono trascorsi 34 anni e nel mondo la fusione fredda continua a coinvolgere molti ricercatori e istituzioni di ricerca che negli anni hanno contribuito a consolidare il risultato dell’eccesso di calore nonostante le difficoltà di riproducibilità, scarsità di finanziamenti, assenza di una teoria consolidata che giustifichi una serie di processi come la fusione fredda, oggi classificati in LENR (Low Energy Nuclear Reactions). Il Museo Primo Levi del Dipartimento di Chimica dell’Università di Roma La Sapienza mostra in questa serie di video la ricerca sulla Fusione Fredda svolta nel Dipartimento dal 1989 al 1996 da chimici e fisici nucleari coordinati dal Prof. Daniele Gozzi. È stata una ricerca fuori dalle tematiche tipiche di un Dipartimento di Chimica sia per la dimensione sperimentale sia temporale che ha prodotto risultati che ribadiscono la realtà del fenomeno anche con evidenze inequivocabili ma, purtroppo, insufficienti per definire un quadro esaustivo della materia. La Direzione del Museo Primo Levi, vista la peculiarità di questa attività di oltre trent’anni fa ha ritenuto opportuno che di essa rimanesse traccia nella storia del Dipartimento. |

On March 23, 1989, Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons reported that in a simple electrolysis experiment in heavy water (D2O) with a palladium (Pd) cathode, the heat measured was greater than that produced in the electrolytic dissociation reaction of D2O. If the same experiment was conducted with a platinum (Pt) cathode, the energy balance was zero. Since no conceivable chemical and/or physicochemical effect could be responsible for an energy balance significantly different from zero, they hypothesized nuclear fusion reactions of deuterium nuclei in the Pd structure. Cold fusion was born. The announcement created worldwide: immediate enthusiasm and persistent skepticism. The first because there was a glimpse of the possibility of low-cost and easy-to-produce energy without resorting to hot fusion which, neither then nor today, despite gigantic investments, has not yet produced available energy. The second relates to the poor reproducibility of the phenomenon and above all because nuclear physics does not foresee low energy fusion reactions. The nuclear fusion between nuclei, preferably light ones, requires very high energies which can be obtained either on the Earth, in the collision in the high vacuum of nuclei accelerated in machines such as the LHC at CERN in Geneva, or in stars at temperatures of billions of °C. Thirty-four years have passed, and in the world, cold fusion continues to involve many researchers and research institutions who over the years have contributed to consolidating the result of heat excess despite the difficulties of reproducibility, scarcity of funding, absence of a consolidated theory that justifies a series of processes such as cold fusion, now classified in LENR (Low Energy Nuclear Reactions). The Primo Levi Museum of the Department of Chemistry of the University of Rome La Sapienza shows in this series of videos the research on Cold Fusion carried out in the Department from 1989 to 1996 by chemists and nuclear physicists coordinated by Prof. Daniele Gozzi. It was research outside the typical themes of a Chemistry Department both for the experimental and temporal dimension that produced results reaffirming the reality of the phenomenon even with unequivocal evidence but, unfortunately, they are insufficient to define an exhaustive picture of the whole matter. The Directorate of the Primo Levi Museum, given the peculiarity of this activity of over thirty years ago, deemed it appropriate that traces of it remain in the history of the Department. |

| SCOPRI | DISCOVER |